“Forever kept as wild forest lands:”

A Story Behind the Making of the Adirondack Forest Preserve

This four-part series by Sam Lasher (History and Political Science, ’25) is based on research from the summer of 2023 funded by the Program for Undergraduate Research. Sam spent time both at Bucknell and in the Adirondacks with the guidance of Professor Claire Campbell. Special thanks to the Adirondack Experience for assistance and archival material.

Part 4: “Forever Wild.” A Hopeful Story

In 1885, the state legislature passed the three proposed bills from the Forestry Commission’s Report, creating the Forest Preserve and putting forever wild into law. Only nine years later, in 1894, the state legislature of New York made an amendment to the state constitution. Article VII Section 7 stated: “The lands of the State now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be leased, sold or exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public or private, nor shall the timber thereon be sold, removed or destroyed.”1 This addition to the “forever wild” line of the Forestry Commission report eliminates the option of logging the Forest Preserve, tying up the loose end that Sargent, James, and Shepard had to leave un-tied due to the politics of their time. But could they have anticipated the effect of their language? The exceptional political success of forever wild as a constitutional amendment can be seen in the Adirondacks today: a region almost entirely (re)forested, especially within the Forest Preserve.

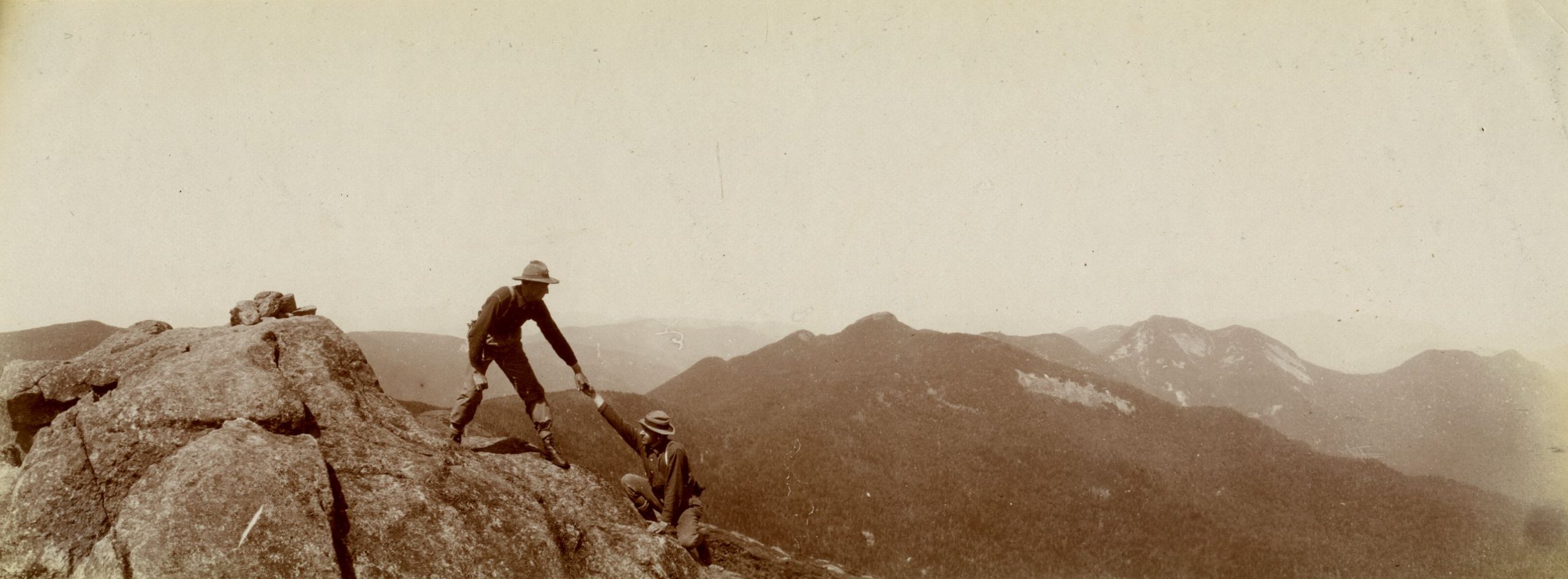

“View from Mount Colden.”

Sam Lasher. 2023. Courtesy of Sam Lasher.

According to Bill McKibben, the new growth has recovered so well it’s hard to tell the difference from the old growth. In fact, he called it “new old growth.”2 Richard Judd explains it as “second nature,” something that has been remade, or (re)forested, but has become so familiar and engrained that we forget it was remade.3 The forever wild idea has led to an Adirondack Park today that is significantly more wild than the Adirondacks that Sargent, James, and Shepard visited in the summer of 1884. Their addition of this line made their report more exceptional and long-standing than they could have ever imagined. They put their ideal ahead of management practices at a time when nature was thought to be for human use. The persuasive language they used to explain the values of the forests, politically allowed them to include the protection offered by the line: “forever kept as wild forest lands.”

Epilogue

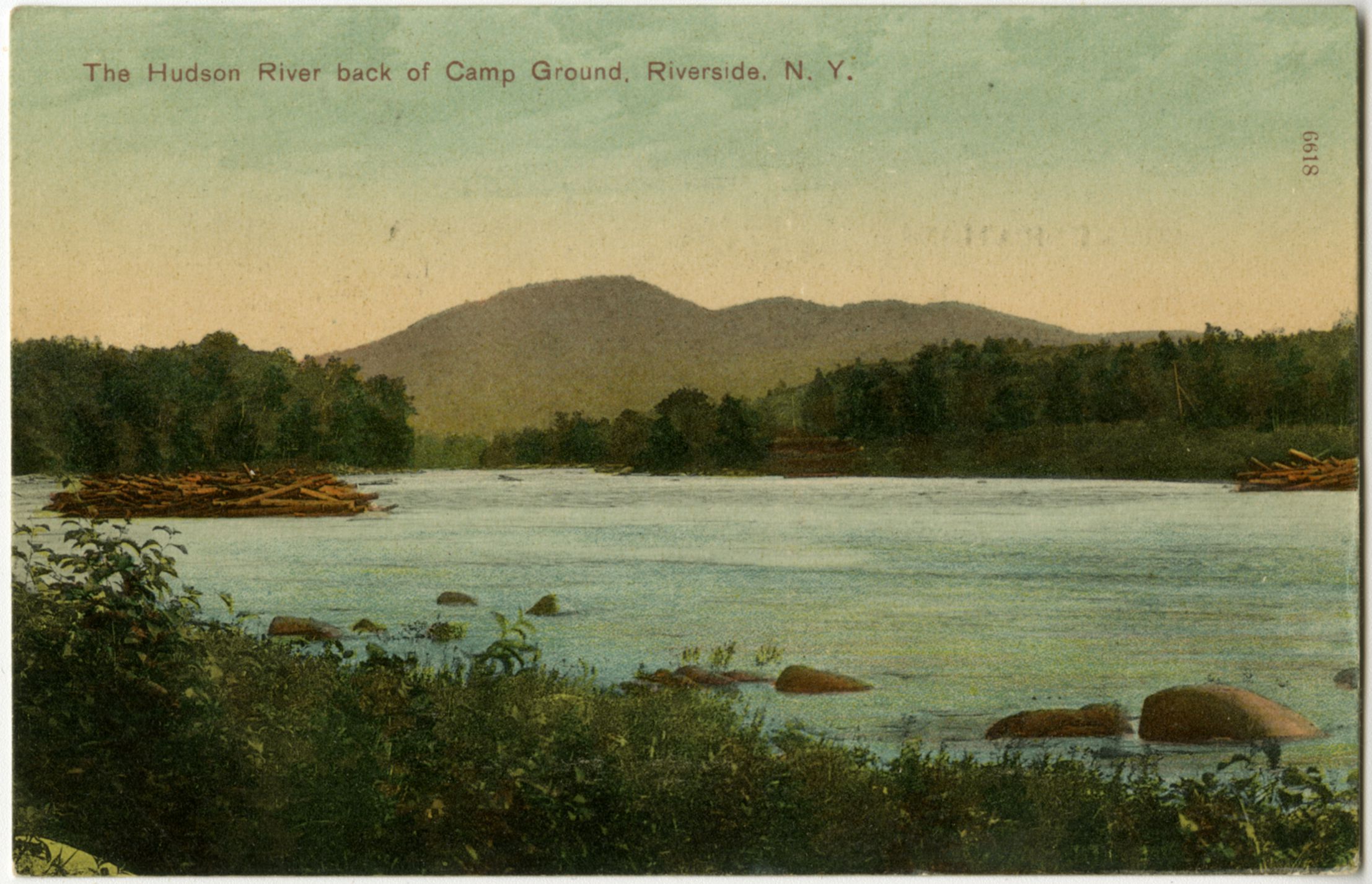

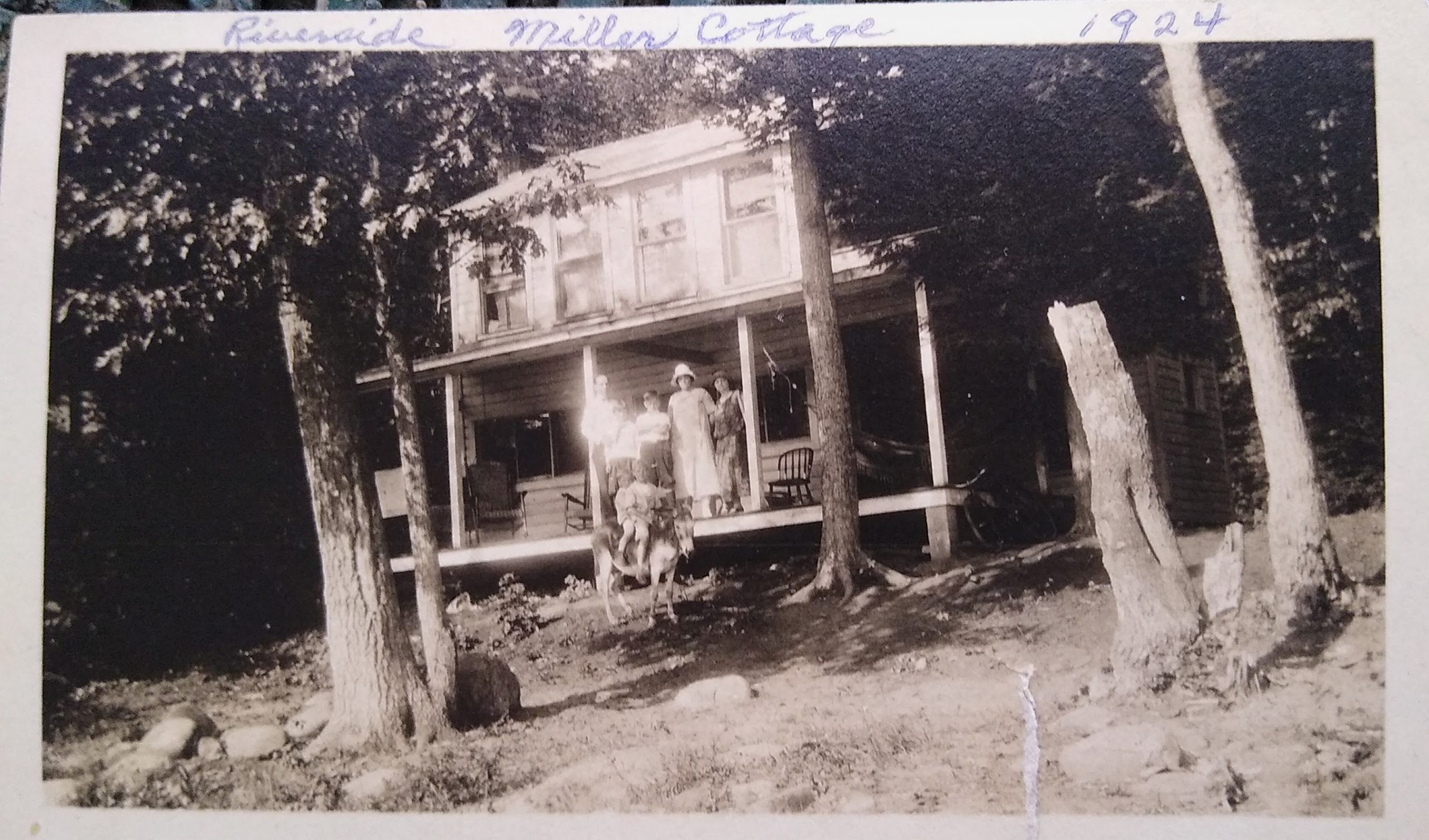

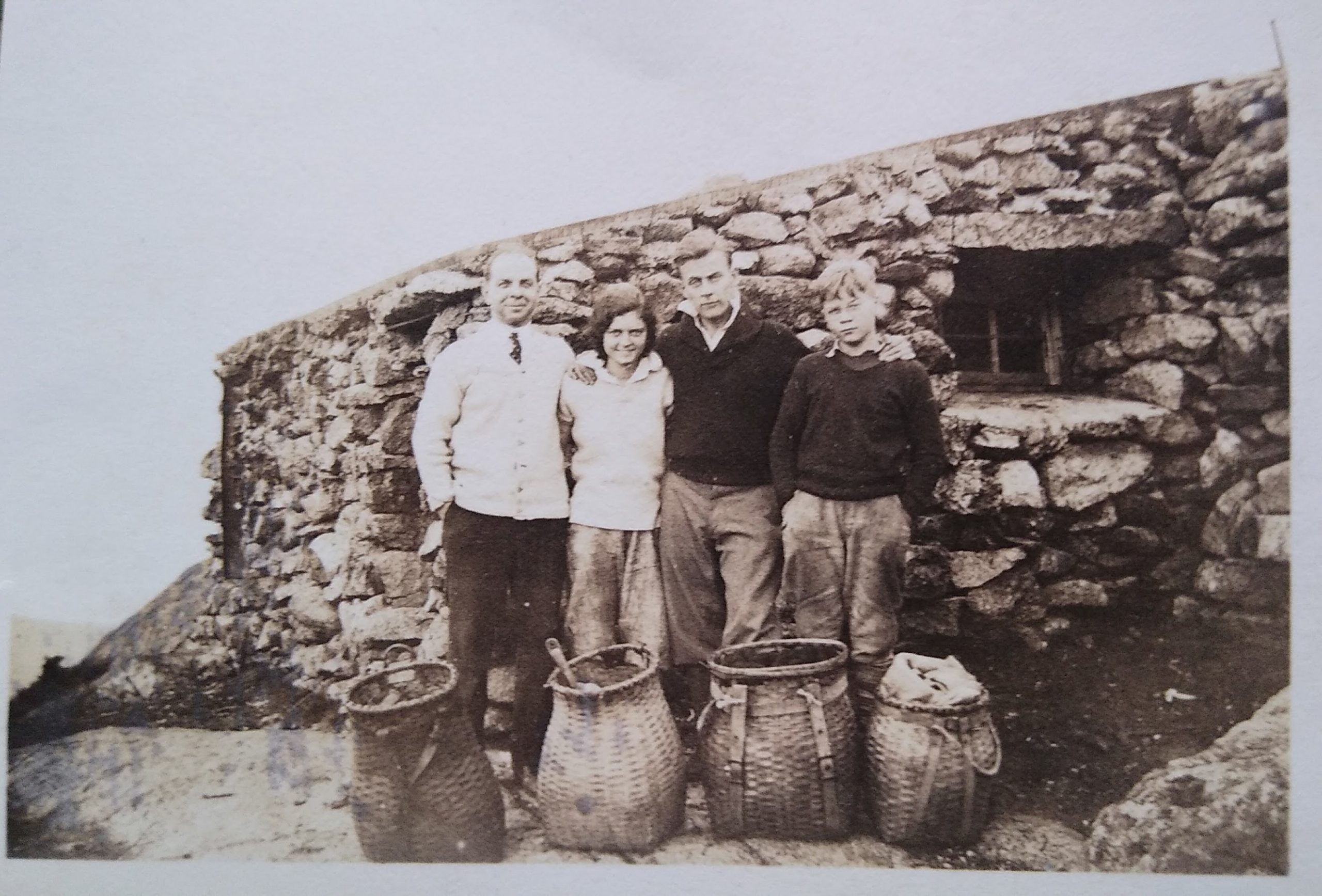

This project has pushed me to recognize the contradiction between my personal deep human history in the Adirondacks and my belief in the hope for “forever wild.” My family first settled in the Adirondacks in 1801 in Bakers Mills and we have had a deep connection to the place since. We were involved at Riverside around the founding in the 1870s and built one of the first cabins around 1900.4 My great-grandmother hiked Mount Marcy (the highest point in New York) in 1930 with her husband, father, and brother. My family was also part of the founding of Skye Farm Camp in 1942, a Methodist summer camp on Sherman Lake.5 We still are very involved there today. My grandparents became Adirondack 46ers in the 1970s, my parents in the 1990s, myself in 2015 at age 12, and my sister in 2022.6 I grew up experiencing the Adirondacks as a series of places that mark my family’s history. I’ve spent a significant amount of my life in the Adirondacks enjoying something that I consider[ed] to be “wild.” In my studies over the past year, my appreciation for the historical origin and promise of the idea of “forever wild” has grown significantly. Yet I am much more conscious of the fundamental contradiction that marks my place in the Adirondacks: believing in “forever wild” while simultaneously leaving my footprints on human-made trails.

Sam Lasher

History and Political Science, ’25

spl013@bucknell.edu

- “Article VII Sec. 7,” in Revised record of the constitutional convention of the state of New York, May 8, 1894, to September 29, 1894, rd. Hon. William H. Steele, Vol. II. (Albany: The Argus Company, Printers, 1900). ↩︎

- Bill McKibben, Hope, Human and Wild : True Stories of Living Lightly on the Earth, 1st ed (Boston: Little, Brown, 1995), 31. ↩︎

- Richard W. Judd, Second Nature: An Environmental History of New England (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 12-14. ↩︎

- Riverside was originally a Methodist summer sermon camp with tent platforms and outdoor church. The tent platforms slowly became cabins and then cottages. Our first cottage was around 1900. My great great grandfather was the first president of the legal organization behind Riverside (Riverside Epworth League Institute), in 1922. He bought our current cottage in 1923 (the original one burned in a fire). ↩︎

- This was an extension of the activities at Riverside about 15 miles away. ↩︎

- The Adirondack 46ers is a club of people that have climbed all 46 mountains over 4,000 feet in the Adirondacks. ↩︎

Bibliography

Campbell, Claire Elizabeth. “Governing a Kingdom: Parks Canada, 1911–2011.” In A Century of Parks Canada, 1911-2011, edited by Claire Elizabeth Campbell, 1-19. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press, 2011.

Jacoby, Karl. Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. 1st ed. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2014.

Judd, Richard W. Second Nature: An Environmental History of New England. University of Massachusetts Press, 2014.

McKibben, Bill. Hope, Human and Wild: True Stories of Living Lightly on the Earth. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995.

Schneider, Paul. The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2016.

Sellars, Richard West. Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. Yale University Press, 1997.

“The Adirondack Park,” Adirondack Park Agency, https://apa.ny.gov/About_Park/index.html.

Van Valkenburgh, Norman J. The Adirondack Forest Preserve: A Narrative of the Evolution of the Adirondack Forest Preserve of New York State. Blue Mountain Lake, N.Y.: Adirondack Museum, 1979.

See “Book jacket language from the 1970 edition of W.H.H. Murray, Adventures in the Wilderness. Edited by William Verner with introduction and notes by Warder H. Cadbury. Syracuse, N.Y.: Adirondack Museum/Syracuse University Press, 1970.

Primary Sources

“Article VII Sec. 7.” Revised record of the constitutional convention of the state of New York, May 8, 1894, to September 29, 1894. Revised by the Hon. William H. Steele, Vol. II. Albany: The Argus Company, Printers, 1900.

Laws of the State of New York. Albany, New York: New York State Legislature, 1884.

Robeson, A. “Map of the Adirondack Plateau showing the position & condition of existing forests.” Forest Commission State of New York, 1884. https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll65/id/7217/rec/1.

Sargent, Charles Sprague, D. Willis James, and Edward Shepard. “The Forestry Commission’s Report.” Assem. Doc. No. 36. of the New York State Legislature, as requested by Chapter 551 of the laws of 1884. Albany, New York: New York State Comptroller’s Office, January 23, 1885, https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/library/F789B001-143E-421D-A93F-366167541520.