“Forever kept as wild forest lands:”

A Story Behind the Making of the Adirondack Forest Preserve

This four-part series by Sam Lasher (History and Political Science, ’25) is based on research from the summer of 2023 funded by the Program for Undergraduate Research. Sam spent time both at Bucknell and in the Adirondacks with the guidance of Professor Claire Campbell. Special thanks to the Adirondack Experience for assistance and archival material.

Part 2: Nature and “Wilderness” in 19th-Century America

During the second half of the nineteenth century, there was a growing conservation movement in North America; however, nature was still considered to be multi-use. Nature could be beautiful in value through tourism and valuable in natural resources like timber, land for cultivation, animals to be hunted, and more. The belief was that nature should be used for the benefit of people, so that even protecting land was “reserving nature for the people’s use.”1 Yellowstone National Park, for example, was created by the US Congress in 1872 with these values and motivations in mind. By protecting the natural and exotic beauty of Yellowstone, railroads and the tourist industry could profit from nature. Roads and hotels were built in the park that could be accessed by the new railroads.2 As Richard Sellars explains, “in an effort to ensure public enjoyment, nature itself would be manipulated in the national parks.”3

“Grand Canon of the Yellowstone.”

1872. Thomas Moran, 1837-1926. Collection: ARTstor Slide Gallery. Source: University of California, San Diego. Original here.

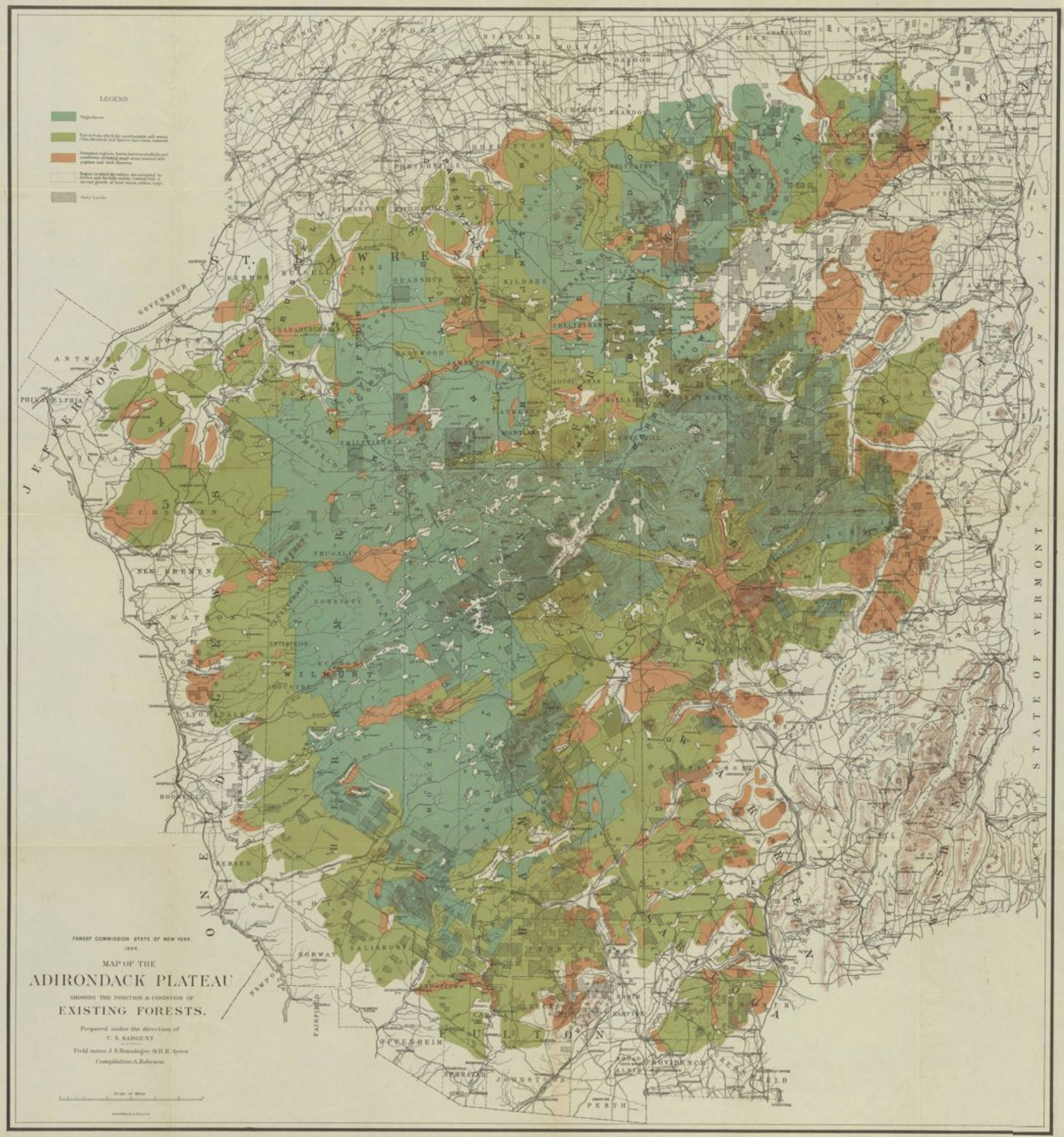

Likewise, at this time in the Adirondacks, there were different groups using nature according to different economic values.4 The Adirondacks were becoming a well-used place; in fact, it’s much less used today than it was in the nineteenth century – a paradox at the heart of this story.5 Logging had become a prominent industry in the Adirondacks due to its vast and dense forests, though, in fact, it was the last region of New York State to be logged due to its rugged mountains, lack of infrastructure, and sandy soil that was bad for agriculture. However, once the loggers developed a system of floating softwood lumber down the numerous rivers they were able to dramatically increase logging in the region. By 1885 it was believed that only around one-third of the old growth forests were still standing, as seen in the attached map. We know now that even less than that were standing at the time.6

“Log Jam”

1888-1938. Ferris Jacob Meigs. Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience.

“Map of the Adirondack Plateau showing the position & condition of existing forests.”

1884. A. Robeson. Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience. See original in New York Heritage Digital Collections: Adirondack Experience, here.

- Green: “Virgin Forest”

- Yellow-Green: “Forest from which the merchantable soft woods (Pine, Hemlock and Spruce) have been removed

- Orange: “Denuded regions, burns (barrens, windfalls and overflows) including small areas covered with poplars and bird cherries)

- Khaki: “Regions in which the valleys are occupied by farms, adn the hills mostly covered with a second growth of hard woods, seldom large.

- Checked: “State Lands”

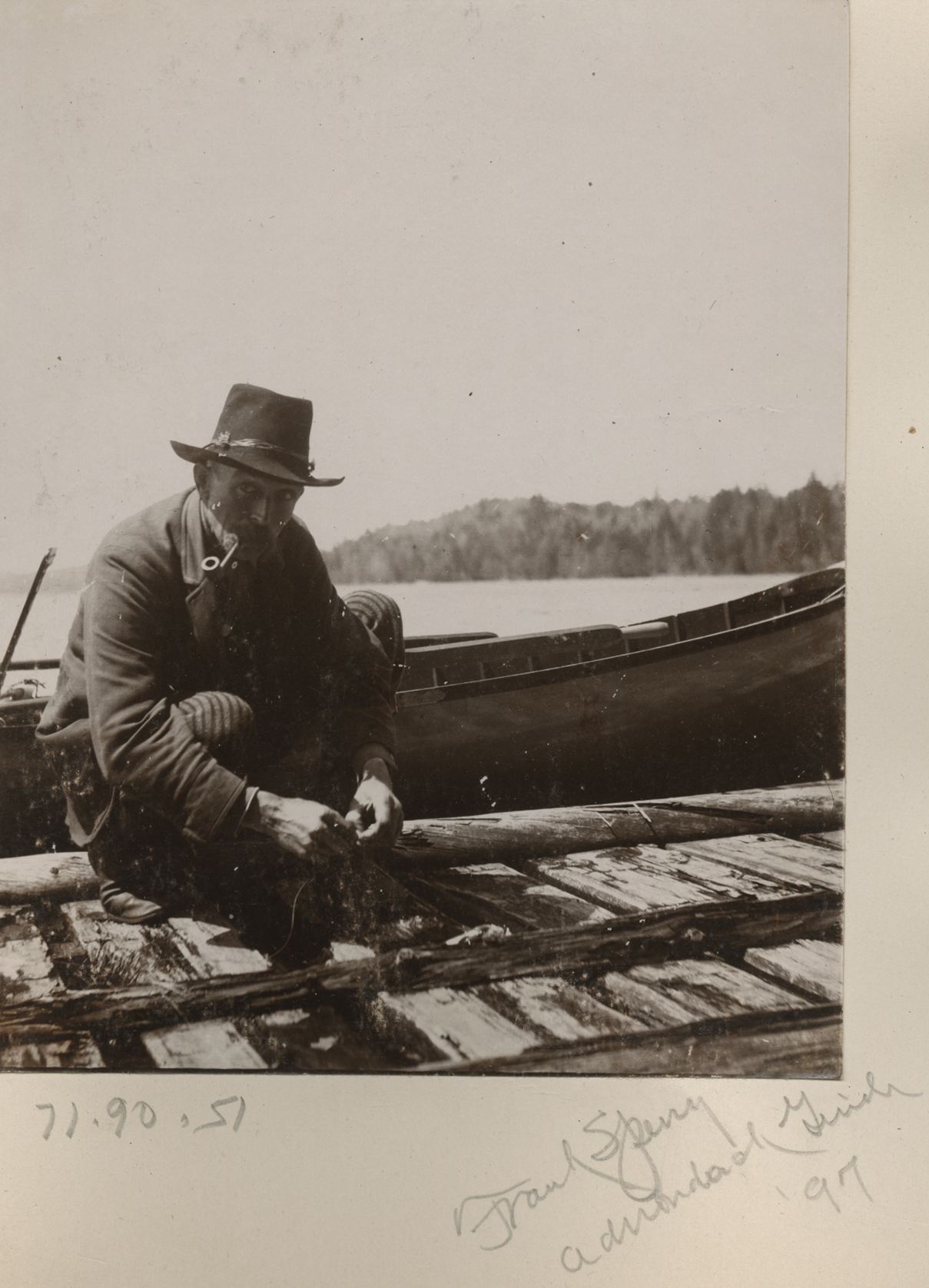

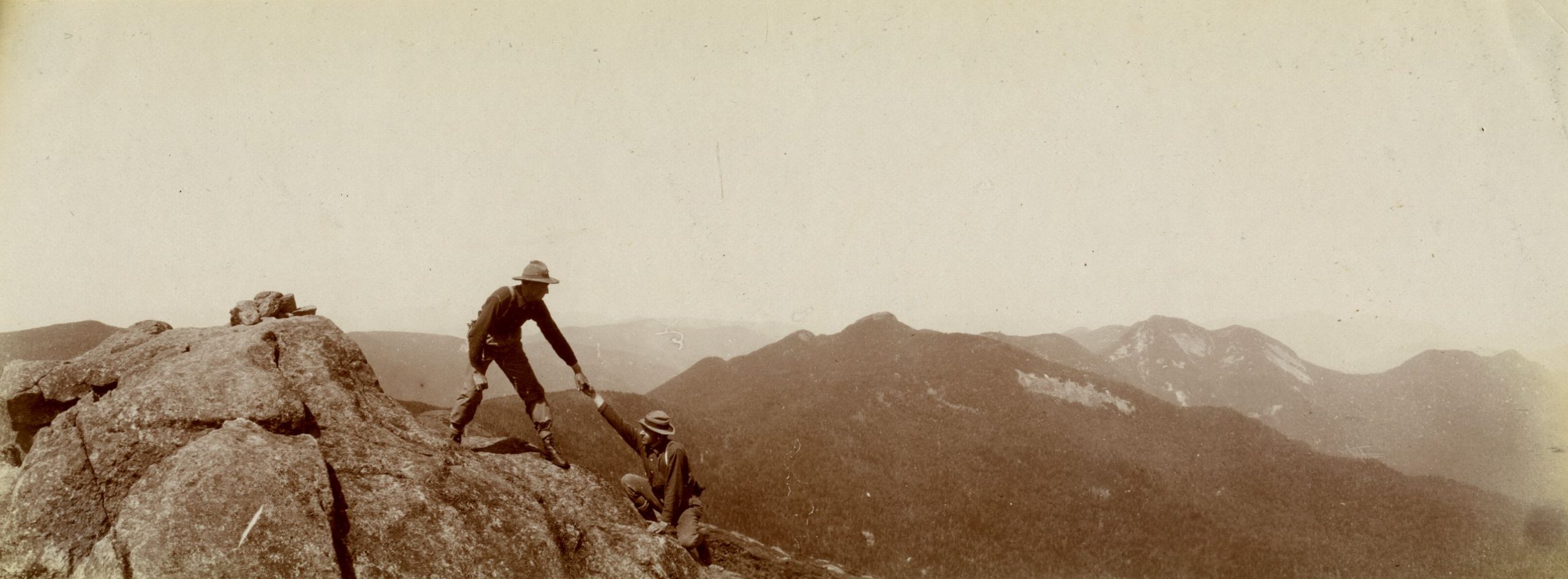

But as long as some portions of the Adirondacks were still untouched by loggers, it was one of the most beautiful, and most conveniently located, places in the country. It looked like the wilderness out West but was only a few hours by train from New York City. In 1869, Adventures in the Wilderness, by William H. H. Murray, was published and is believed to have been a catalyst for the tourism boom in the Adirondacks in the following decades. The next summer, thousands of tourists went to the Adirondacks in what is called “Murray’s Rush.” The train at the time didn’t even reach the park, ending in Glens Falls. Wealthy families from New York City, “Gilded Age men,” built so-called Great Camps and hotels on lakes and rivers that they would visit in the summer months. Adirondack guides (usually local residents) would accommodate their travel with their knowledge of the land and their Adirondack guide boats. There were more than 200 inns and Hotels by 1875, but only a few in 1850. The tourist industry and wealthy Great Camp owners valued the Adirondacks for its beauty and attractiveness, not its resource value.

The Adirondacks were, in short, heavily used by 1885 – not a wilderness, but a measure of how nature was valued in Gilded Age America, whether material or aesthetic. When the state legislature asked for experts “to investigate and report a system of forest preservation” in 1884, they were asking in terms of forest preservation for future human use, or sustainable harvest. What Sargent and the other authors would suggest, however, was an emerging idea; protecting land, not for future use, or as they put it, that these forests “shall be forever kept as wild forest lands.” The authors of this report imagined a better future – on a longer timescale – for the forests that were valued by so many.

Sam Lasher

History and Political Science, ’25

spl013@bucknell.edu

- Claire Elizabeth Campbell, “Governing a Kingdom: Parks Canada, 1911–2011,” in A Century of Parks Canada, 1911-2011, ed. Claire Elizabeth Campbell (Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press, 2011), 4. ↩︎

- Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (Yale University Press, 1997), 10. ↩︎

- Sellars, Preserving Nature, 11.. ↩︎

- This region belongs to the traditional lands of the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee people); it is telling and representative of conservation/park language at this time that the report does not acknowledge this other history and groups of occupants. I plan to do more research of Indigenous history in the Adirondack region in the future. ↩︎

- As seen in the attached photographs. ↩︎

- Norman J. Van Valkenburgh, The Adirondack Forest Preserve : A Narrative of the Evolution of the Adirondack Forest Preserve of New York State (Blue Mountain Lake, N.Y.: Adirondack Museum, 1979), 34-35. ↩︎