“Forever kept as wild forest lands:”

A Story Behind the Making of the Adirondack Forest Preserve

This four-part series by Sam Lasher (History and Political Science, ’25) is based on research from the summer of 2023 funded by the Program for Undergraduate Research. Sam spent time both at Bucknell and in the Adirondacks with the guidance of Professor Claire Campbell. Special thanks to the Adirondack Experience for assistance and archival material.

Part 3: The Forestry Commission’s Report

The Forestry Commission’s Report and its recommendations led the state legislature to create the Adirondack Forest Preserve in 1885. This, in turn, set the foundation for the creation of the Adirondack Park in 1892, which was reinforced by an 1894 state constitutional amendment that gave the park and the forest preserve exceptional standing and protection. This report to the legislature shows how those considered experts on the subject of forestry and public lands were able to persuade, using dramatic and descriptive language along with a map and photographs, a hesitant legislature into passing exceptional legislation that claims the forest preserve and any added state lands should be “forever kept as wild forest lands.”1 While that statement might have become the best-known part of the report, the first twenty-eight pages extensively discuss the situation of the Adirondacks and all of the values that various groups cared about. So it is worth spending some time looking at this report more closely.

Over the summer of 1884, Sargent, James, and Shepard made “repeated visits, [to] the Adirondack Forests.”2 According to the Comptroller, they did “their work actively and zealously without pay.”3 They reported that there were so many issues with identifying land ownership that they suggested to “consider the forests without regard to ownership.”4 It was actually quite common that state lands would be illegally logged and then burned to cover up the evidence.5 Within the state land that they could identify, there were still some parcels of old growth forest, a lot of partially logged forest, and “considerable areas of these lands entirely stripped of forest covering.”6 This can be seen on the “Map of the Adirondack Plateau showing the position & condition of existing forests” from 1884.7 The causes of forest destruction included logging, forest fires (usually human-caused), and agriculture. They believed that “certain regions of the earth’s surface are adapted by nature to remain covered with forests, and that any attempt to devote such regions to other purposes can only be followed by failure and disaster. The people of New York have not yet learned this lesson.”8

“Map of the Adirondack Plateau showing the position & condition of existing forests.”

1884. A. Robeson. Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience. See original in New York Heritage Digital Collections: Adirondack Experience, here.

- Green: “Virgin Forest”

- Yellow-Green: “Forest from which the merchantable soft woods (Pine, Hemlock and Spruce) have been removed

- Orange: “Denuded regions, burns (barrens, windfalls and overflows) including small areas covered with poplars and bird cherries)

- Khaki: “Regions in which the valleys are occupied by farms, and the hills mostly covered with a second growth of hard woods, seldom large.

- Checked: “State Lands”

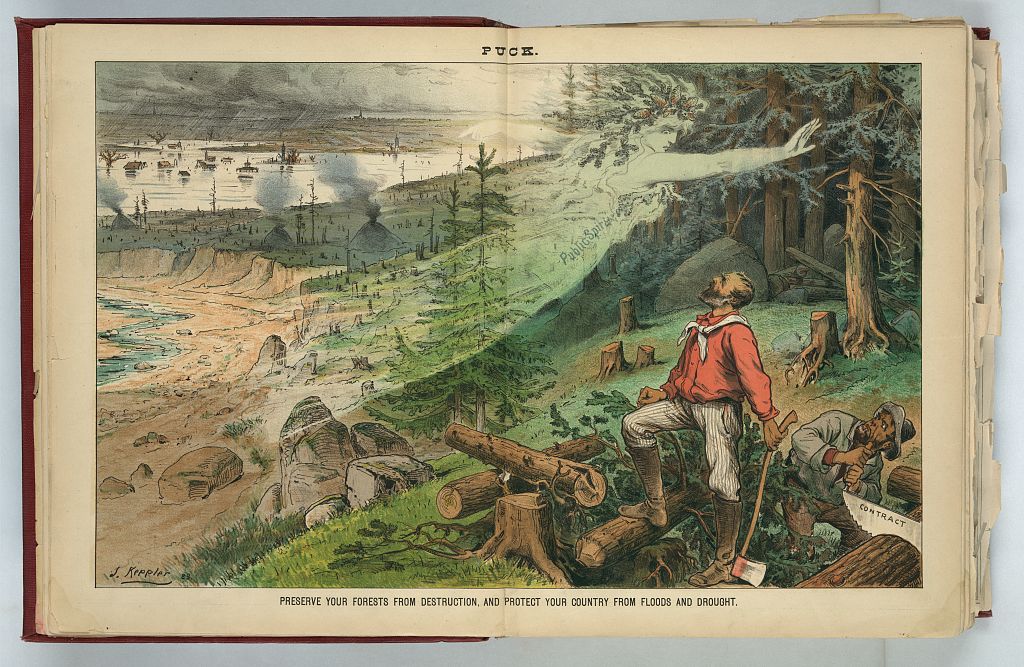

The authors emphasized the economic value of the forests and that their “extermination will reduce this whole region to an unproductive and dangerous desert.”9 Their dramatization of the extermination of forests, along with their focus on value, was politically persuasive towards the legislature, but it was also not far from the truth. Continued logging of the Adirondack forests would have “deprived [the Adirondack region] of its only permanent source of wealth, and its inhabitants must gradually sink into a condition of great misery and dependence. Its future lies in the Adirondack forests; if these are destroyed, its prosperity will disappear forever.”10

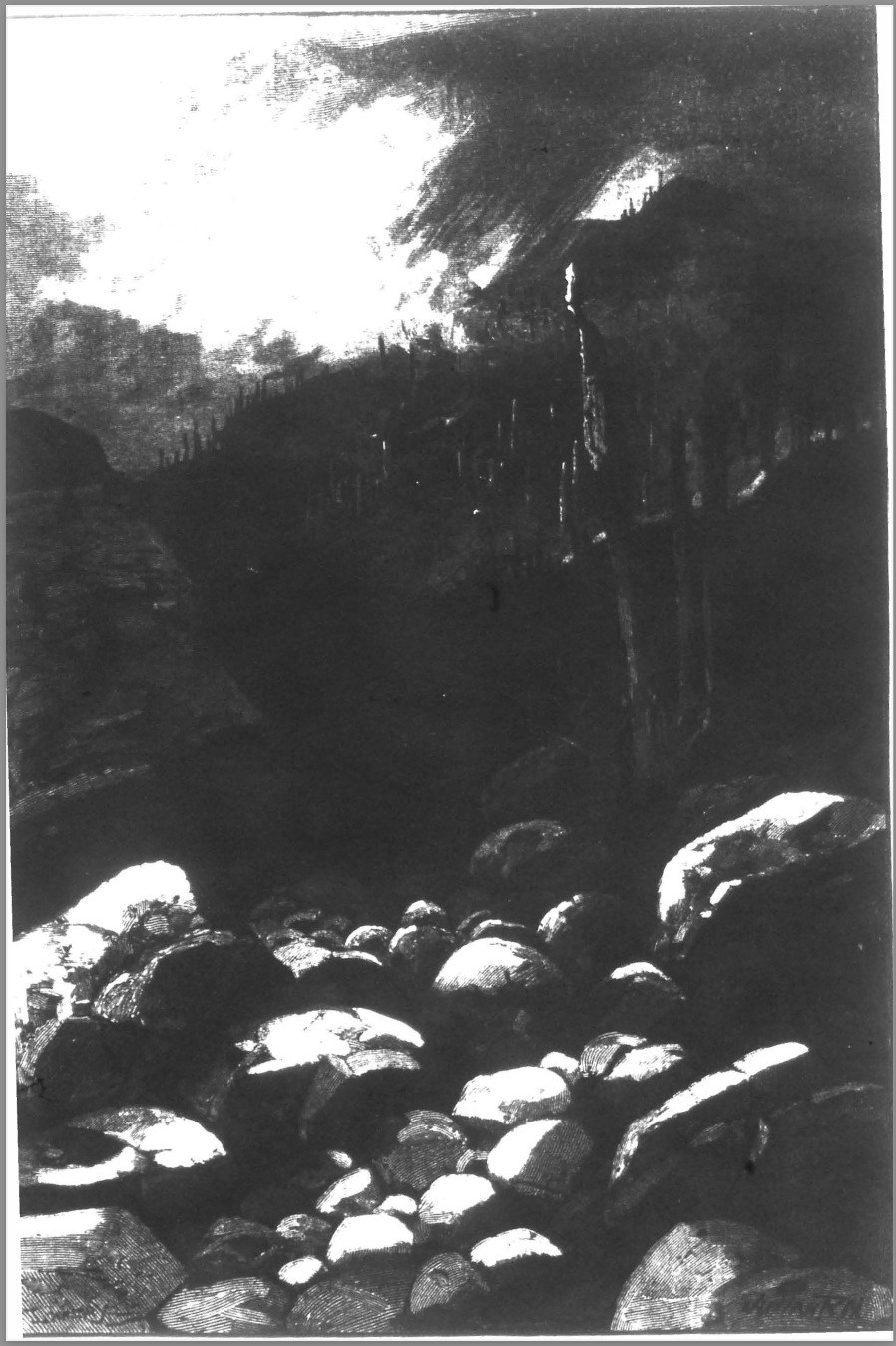

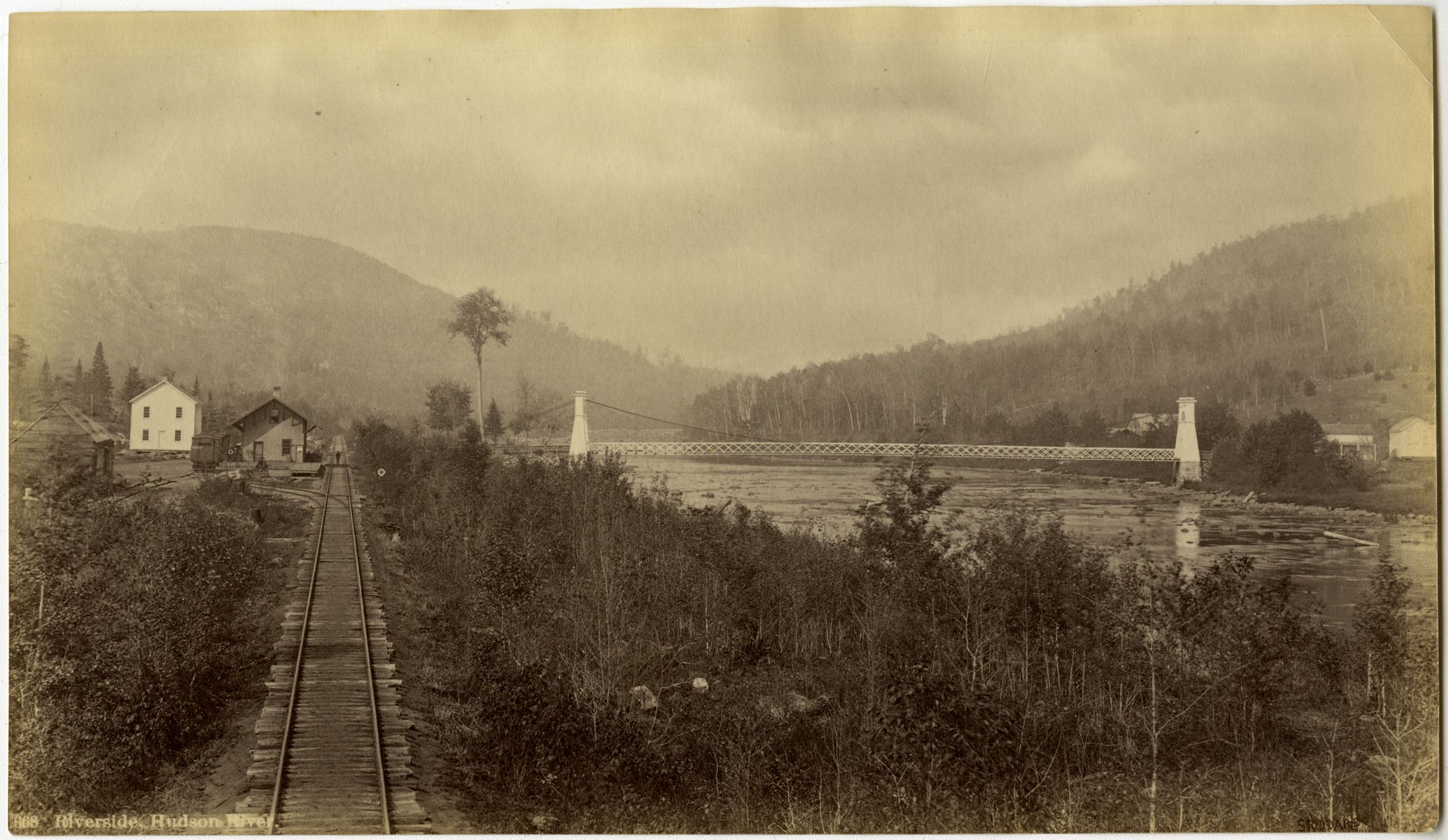

There were three uses of the Adirondack forests that Sargent and the others focus on: the forests as “reservoirs of moisture” and the source of rivers, the forests’ attractiveness and tourism, and the value of timber. The Adirondack Plateau is a source of the Saint Lawrence River to the north, the Mohawk River to the southwest, and the Hudson River to the south. The region gets more rainfall than the rest of the state, allowing it to supply its rivers with a steady flow of clean water throughout the year. The forests act as “reservoirs of moisture,” holding the water back so that even in the driest parts of the summer the rivers are still flowing. Cutting down the forests led to decreases in water flow by as much as 30-50% according to locals at the time. Even with railroads expanding into the region, navigable rivers like the Hudson and Mohawk/Erie Canal were still economically important and “essential to the continued prosperity of the state… Their destruction must be followed by widespread commercial disaster.”11

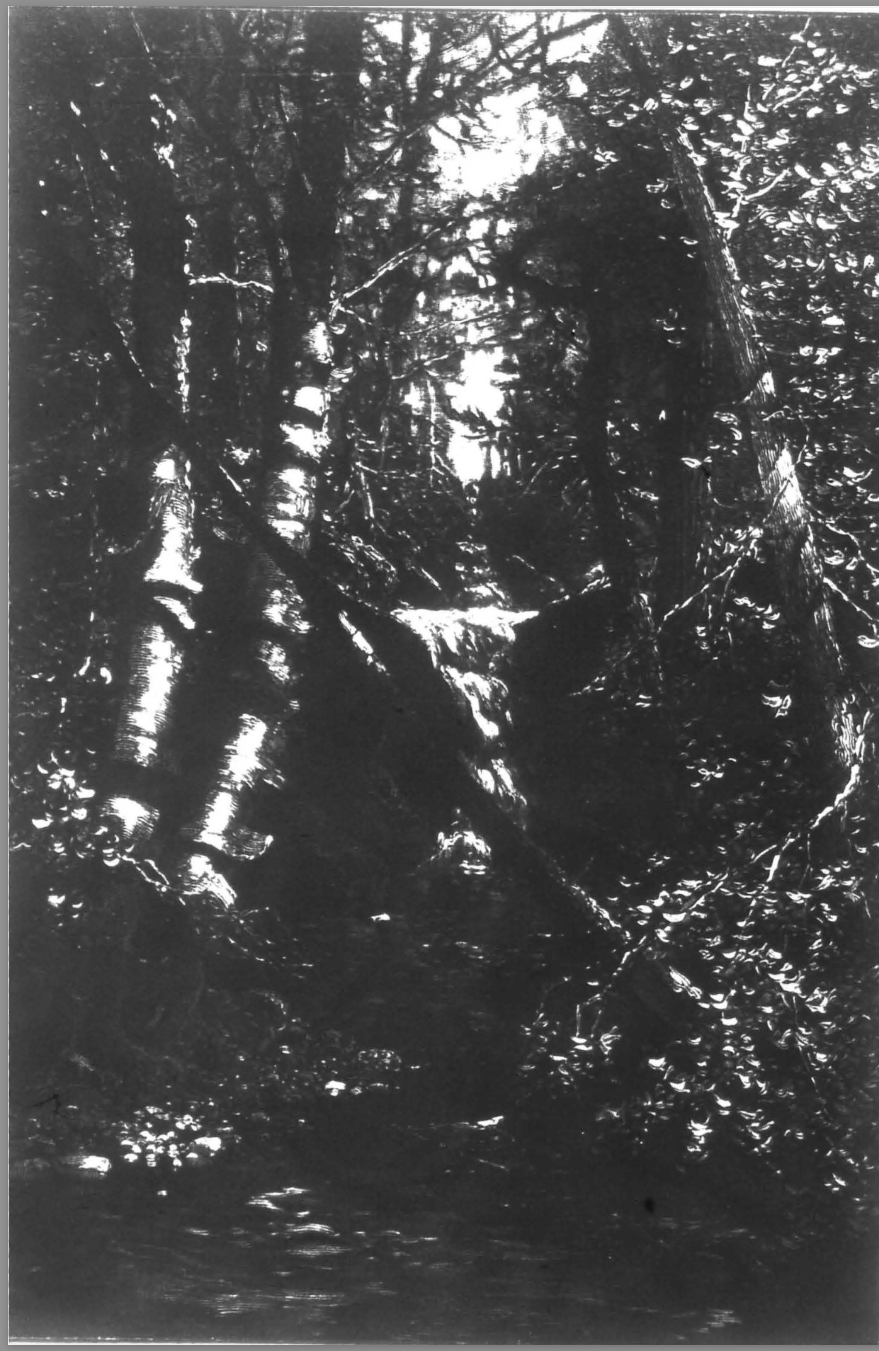

The report also explains how the established and growing tourism industry in the Adirondacks “is dependent upon the existence of the forests. They make the Adirondack region attractive… and supply the element of wildness,- the charm which draws people to visit the region.” Just like Yellowstone, the beauty and attractiveness of the forests allowed tourism to be a “lucrative business” that had “millions of dollars” invested in it by many influential Gilded Age men. It was also so close to New York City that “nowhere else in the United States can this object be more freely or easily accomplished.” The authors argued that the continued destruction of the forests would eliminate the growing tourism industry and “the public will be deprived of the opportunity to enjoy the benefits which a visit to the Adirondack woods now offers.”12 The same public that votes the legislature into office.

“Taylor House”

1870-1900. Seneca Ray Stoddard, 1844-1917. Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience.

Sargent, James, and Shepard discuss lumbering in the report with great caution. They acknowledge the economic value of logging softwood trees for lumber. They suggest that with the right forest management, logging of softwoods can happen without forest destruction.13 The logging companies would not do this on their own, though; “the future permanence of these forests cannot be absolutely insured except through state ownership and control.”14 The logging companies were not paying their taxes, leaving branches on the ground (which dramatically increased the risk of forest fires), and expanded railroads in order to remove hardwoods.15 Without government forest management the whole of the forests was at risk.

In order to protect the forests and the constellation of values that they held, Sargent, James, and Shepard proposed three bills to the legislature. One of the proposed bills focused on taxes, including ending the tax loophole that allowed logging companies to avoid their taxes and then let the state acquire their land to pay for the taxes after they had been logging it for five to ten years.16 Another proposed bill focused on the protection of forests from forest fires. It suggested that starting a forest fire should be a misdemeanor punishable by six months in prison or a fine of up to two hundred and fifty dollars. It increased the protection of public lands but also the protection of private property, a trend that continues today.17

The third and most significant bill proposed by the Forestry Commission created the Forest Preserve and the Forest Commission, which would manage the Forest Preserve and facilitate adding lands in the future.18 The Forest Preserve included all state lands in the Adirondack counties, totaling over 750,000 acres.19 Government control and management of forests had “never been attempted in the United States” at this scale; in fact, there was no forest management policy before 1885 in the Adirondacks.20 The introduction to the bill states the importance of rivers and “that the Adirondack forests should be preserved, and that the lands in their vicinity which are not fit for tillage should become and remain covered with forest trees.” This line, and the bill, carefully contradict their discussion about logging. The bill starts with the creation of the forest preserve. It then states that

The lands now or hereafter constituting the forest preserve shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be sold or leased except as hereinafter provided, or taken or used by any public officer, or by any person or corporation, public or private, except as herein especially provided, under the permission of the Forest Commission.21

Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 39.

This report is in many ways a product of its time and nineteenth-century views of North American lands as “natural resources”; but this line is quite exceptional. The Commissioners were arguing for a new Forest Preserve that consisted of lands that “have fallen into the ownership of the State simply because they have been stripped of their merchantable timber and rendered waste, and for many years to come practically valueless.” While their report emphasizes the protection of the value of the Adirondack forests, this line suggests that the forests should be protected whether for future use or not – and suggested that there might be value in lands apart from human use. The forever wild idea started with this report but the authors would have never predicted how important and long-standing it would be.

“Thomas Mountain.”

Sam Lasher. 2023. Courtesy of Sam Lasher.

Sam Lasher

History and Political Science, ’25

spl013@bucknell.edu

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 39. ↩︎

- Van Valkenburgh, The Adirondack Forest Preserve, 32. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 1. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 4, This did happen in 1892 with the creation of the Adirondack park that has more protection over forests on private lands. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 12. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 4. ↩︎

- A. Robeson, “Map of the Adirondack Plateau showing the position & condition of existing forests,” Forest Commission State of New York, 1884, https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16694coll65/id/7217/rec/1. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 5-6. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 6. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 9-10. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 6-8. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 8-9. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 9-12. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 16. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 15, hardwood is too heavy to float down the rivers so it had to be removed by stagecoaches and trains. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 50-57, the bill also changed taxes so that every tax payer in New York State contributed to the management of the forest preserve. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 46-49. ↩︎

- However, the authors did not recommend condemnation of the lands due to “public sentiment.” They also felt that it was important to develop a good system of management before they actively increased the size of the preserve since forest management had never been attempted at this scale. Report page 17 ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 4. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 17. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 39. ↩︎