“Forever kept as wild forest lands.”

A Story Behind the Making of the Adirondack Forest Preserve

This four-part series by Sam Lasher (History and Political Science, ’25) is based on research from the summer of 2023 funded by the Program for Undergraduate Research. Sam spent time both at Bucknell and in the Adirondacks with the guidance of Professor Claire Campbell. Special thanks to the Adirondack Experience for assistance and archival material.

Part 1: An Unexpected Beginning

In January 1884 the New York State Senate received a report on state lands from a special committee on state lands in the Adirondack region. According to the report, between 1873 and 1883 New York State went from owning 38,854 acres of land to 750,616 acres of land, almost entirely on the Adirondack Plateau.1 The state had acquired this land, in some ways, unintentionally, through unpaid taxes.2 (Logging companies were harvesting the trees, not paying their taxes, and then – after five or ten years – letting the state acquire their land to cover the unpaid taxes.)3 The state now owned all of this “valueless” and barren land, and needed a system of managing it. It was deemed not suitable for agriculture due to its rocky/sandy soil and long winters; the forests were, presumably, the only value. 4

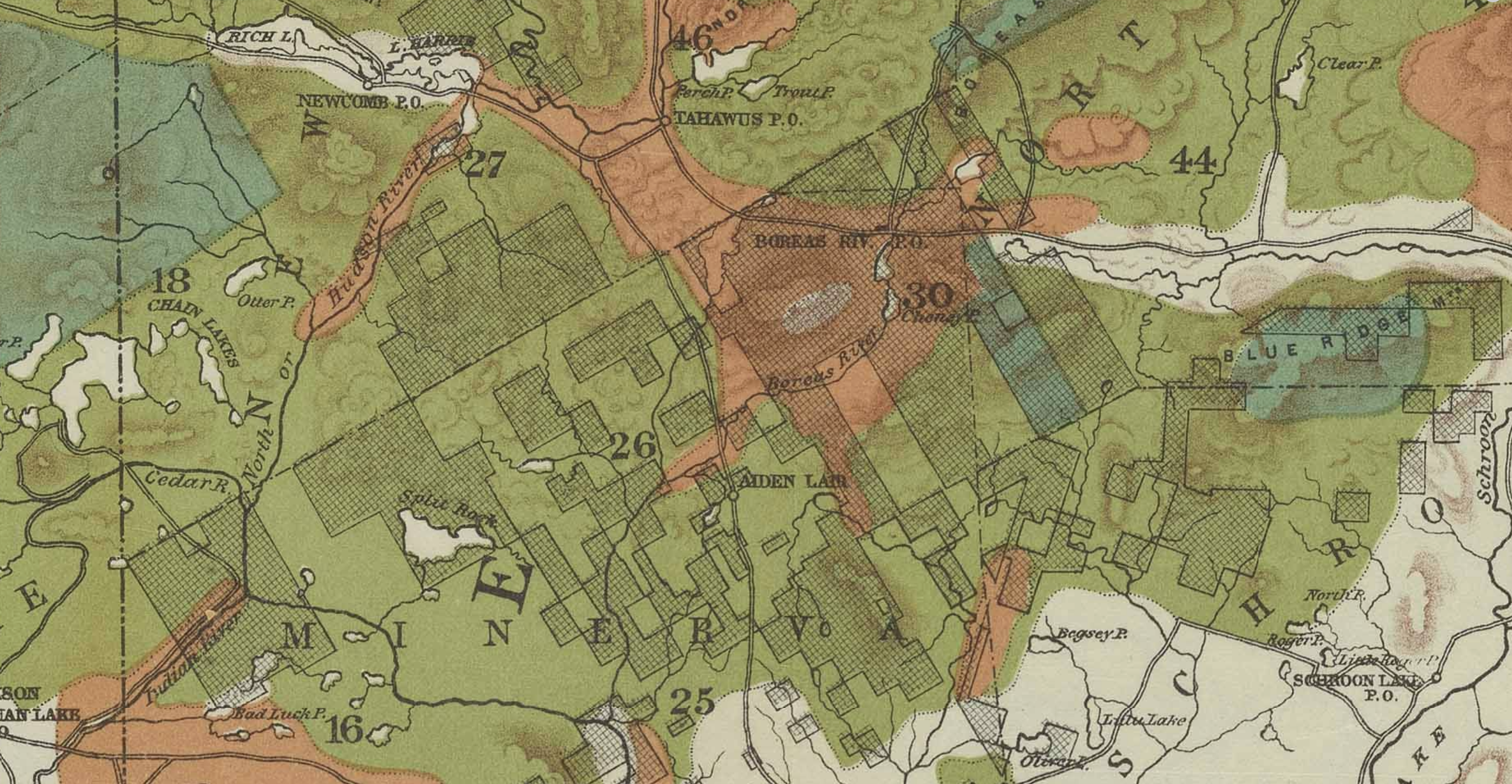

“Map of the Adirondack Plateau showing the position & condition of existing forests.”

1884. A. Robeson. Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience. See original in New York Heritage Digital Collections: Adirondack Experience, here.

- Green: “Virgin Forest”

- Yellow-Green: “Forest from which the merchantable soft woods (Pine, Hemlock and Spruce) have been removed

- Orange: “Denuded regions, burns (barrens, windfalls and overflows) including small areas covered with poplars and bird cherries)

- Khaki: “Regions in which the valleys are occupied by farms, adn the hills mostly covered with a second growth of hard woods, seldom large.

- Checked: “State Lands”

That year, the state legislature set aside $5,000 to the comptroller “for the employment of such experts as he may deem necessary to investigate and report a system of forest preservation.”5 Over the next year the new Forestry Commission – including Professor Charles Sprague Sargent of Harvard University,6 D. Willis James, a businessman of New York City, Edward Shepard, an attorney from Brooklyn, and Hon. William A. Poucher,7 a judge from Oswego – made various trips to the Adirondack Plateau “to report a system of forestry.”8 They presented their report to the state legislature on January 23, 1885, a year after the legislature learned of the massive amount of land now in state hands.9 Within a year, the legislature passed various laws to create the forest preserve – the exact laws that were proposed by the report in 1885.10 This was a remarkable arc of exploration and action within two short years in American environmental history. This course of events begs the question: are the Adirondacks exceptional? What made this possible?

“New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Massachusetts & Connecticut.”

Published by A. & C. Black. Edinburgh. 1856. Printed in Colours by Schenck & Macfariane. Edinburgh. Drawn & Engraved by J. Bartholomew, Edinburgh. Courtesy of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

The Forestry Commission’s Report has been glossed over by many historians of Adirondack history.11 However, this report was evidently extremely persuasive and influential in the protection of the Adirondacks. Today the Adirondack Park is around 6 million acres with around 2.6 million acres included in the forest preserve. The Adirondack Park Agency regulates the private land in the park as well. Located in the northeast corner of New York State, it is “the largest publicly protected area in the contiguous United States, greater in size than Yellowstone, Everglades, Glacier, and Grand Canyon National Park combined.”12 So how did this bureaucratic report have such an immediate and long-standing impact?

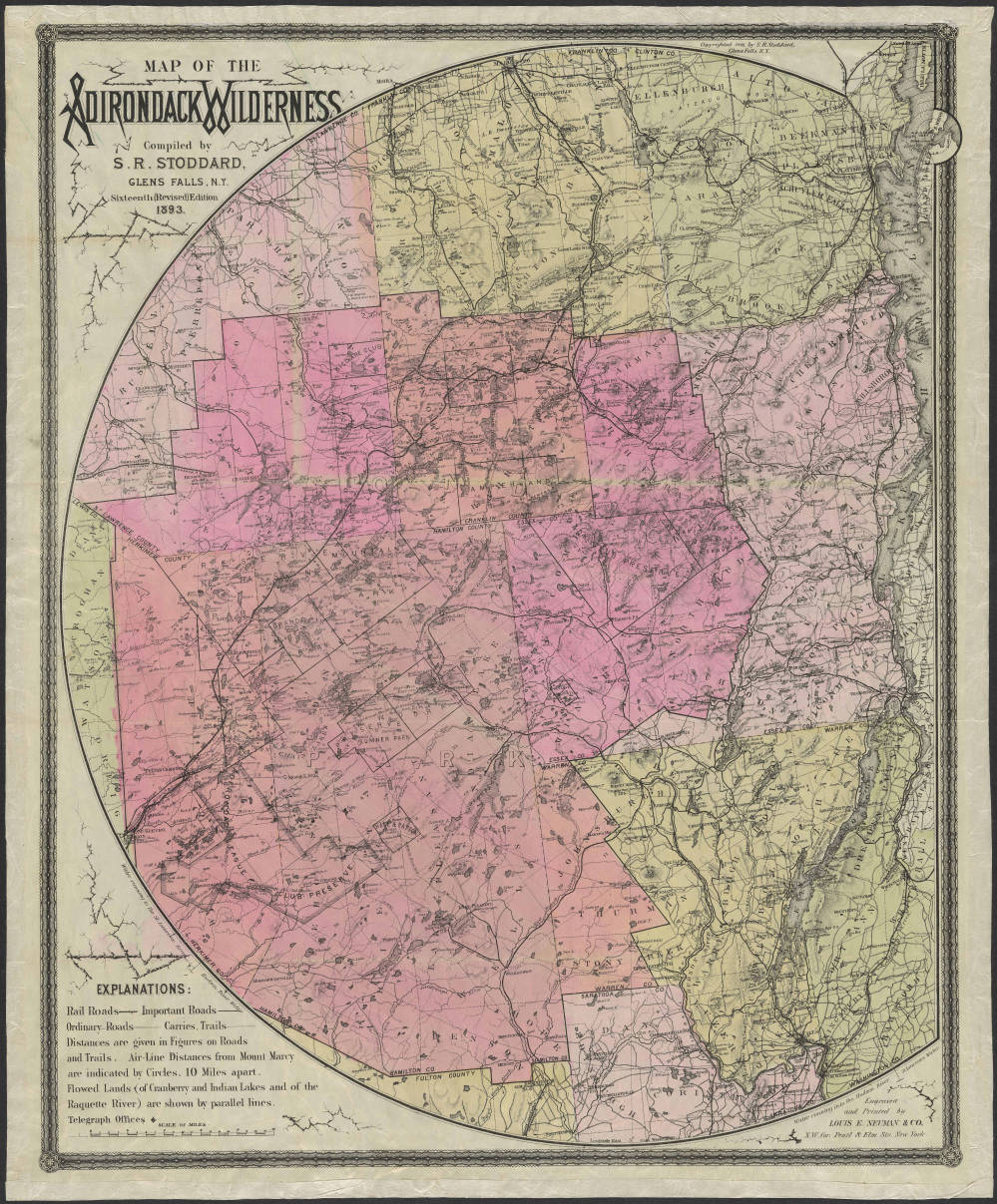

“Map of the Adirondack Wilderness”1893. Seneca Ray Stoddard.

Courtesy of the Adirondack Experience. See original in New York Heritage Digital Collections: Adirondack Experience, here.

Sam Lasher

History and Political Science, ’25

spl013@bucknell.edu

- Charles Sprague Sargent, D. Willis James, and Edward Shepard, “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” Assem. Doc. No. 36. of the New York State Legislature, as requested by Chapter 551 of the laws of 1884 (Albany, New York: New York State Comptroller’s Office, January 23, 1885), 21, https://adirondack.pastperfectonline.com/library/F789B001-143E-421D-A93F-366167541520. ↩︎

- Today, New York State owns 2.6 million acres in the Adirondacks, making this initial increase in public land ownership in the region founding to what would later become the Adirondack Park in 1892. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 21-22. ↩︎

- Karl Jacoby, Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation, 1st ed. (Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2014), 12. ↩︎

- Laws of the State of New York (Albany, New York: New York State Legislature, 1884), Ch. 551, 723. ↩︎

- Sargent was a leading expert on forest and later worked with John Muir as the chairman of the National Forestry Commission. “Charles Sprague Sargent,” The John Muir Exhibit, Sierra Club, latest modified 2023, https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/people/sargent.aspx. ↩︎

- Judge Poucher later had a falling out with the three other authors of the report and never signed off on it due to a disagreement on “administrative method” of the forest commission. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 1-2. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 1-3, the 1885 Forestry Commission Report to the legislature (Assem. Doc. No. 36) will now be referred to as “The Forestry Commission’s Report.” Not to be mistaken with the Forest Commission’s First Annual Report of 1885. ↩︎

- Sargent et al., “The Forestry Commission’s Report,” 39-57. ↩︎

- Other authors have briefly mentioned the report, relying primarily on the phrase “unproductive and dangerous desert” and the exceptional “forever kept as wild forest lands,” but without closely examining the source itself. See, for example, Paul Schneider, The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness, 223-225, and Paul Schaefer, Defending the Wilderness: The Adirondack Writings of Paul Schaefer (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1989). Norman J. Van Valkenburgh has a more thorough analysis of the report, but emphasizes the legal processes of land acquisition more than historical context; see The Adirondack Forest Preserve : A Narrative of the Evolution of the Adirondack Forest Preserve of New York State (Blue Mountain Lake, N.Y.: Adirondack Museum, 1979), and Norman J. Van Valkenburgh, Land Acquisition for New York State: An Historical Perspective (Arkville N.Y: Catskill Center for Conservation and Development, 1985). ↩︎

- “The Adirondack Park,” Adirondack Park Agency, https://apa.ny.gov/About_Park/index.html. ↩︎